The Quest for Truth: The Tangled Web of Epistemology

From Ancient Philosophers to Modern Crises, How Do We Know What We Know?

I’m pretty sure I’ve mentioned once or twice in my recent posts that I’ve been planning to write about epistemology. It sure has been on my mind a lot for the past few weeks and the more I look into it and think about it, the more complicated it seems.

We recently had guests – a young couple - and, over supper, I was asked what I was working on. I said that I was thinking about – not actually working on – epistemology. The husband and wife looked at each other and exchanged some sort of silent communication which she then explained. Apparently, her father, a professor at a university, has been writing a book about epistemology for the past 40 years. I thought, ‘holy frijoles!’ I worked on the research for my book on early Christianity – off and on - from about 1982 until it was finally completed in 2020. That’s only 38 years and I’m satisfied with the work I did on that. But this poor guy –the father of our guest- has been working on epistemology longer than that and is still laboring with, apparently, no end in sight.

So, I did a lot more thinking and poking into the matter. Naturally Grok got a real workout with me sending it out to fetch data to help me think even harder. I am no longer surprised that someone can work on this topic for 40 years with no end in sight.

What is Epistemology and What Does it Do?

The word epistemology comes from the Greek words epistēmē (ἐπιστήμη), meaning “knowledge” or “understanding,” and logos (λόγος), meaning “study” or “discourse.” So, epistemology literally means the study of knowledge. (It’s not related to the word ‘epistle’; they only share a prefix: epi.)

Epistemologists are philosophers who specialize in epistemology, the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origins, scope, and limits of knowledge. Their work primarily involves analyzing fundamental questions such as: What constitutes knowledge? How do we distinguish between justified beliefs and mere opinions? What are the sources of knowledge (e.g., perception, reason, memory, or testimony)? And how can we respond to skepticism about whether we can truly know anything at all?

In practice, epistemologists engage in a range of activities:

They develop theories and arguments about concepts like belief, truth, justification, and evidence. For instance, they might debate whether knowledge requires certainty or if it’s possible to have knowledge without absolute proof, often using thought experiments.

Many epistemologists are academics who lecture at universities, design courses on philosophy of knowledge, and mentor students in critical thinking and logical reasoning.

They collaborate with fields like cognitive science, artificial intelligence, law, or education to apply epistemological insights, such as evaluating the reliability of eyewitness testimony or the ethics of belief in misinformation eras.

Overall, their role is more theoretical than practical; they aim to clarify how humans achieve cognitive success (accurate understanding) and avoid failure (false beliefs or ignorance), rather than conducting empirical experiments like scientists.

Epistemology affects the average person in subtle but profound ways, influencing how we navigate information, make decisions, and interact with the world. Epistemological principles guide how we assess risks, form opinions, and learn from experience. For example, when deciding whether to trust a medical treatment, we implicitly draw on ideas of evidence and justification to weigh expert opinions against personal anecdotes. In politics, it affects how we view authority and propaganda; in relationships, it influences trust and communication by prompting reflection on biases or assumptions. Without epistemological awareness, people might fall into echo chambers or dogmatism, leading to poorer outcomes in personal or professional life. It informs fields like science (e.g., the scientific method relies on empirical justification) and law (e.g., standards of evidence in trials), which in turn structure institutions that impact daily routines, from healthcare policies to consumer protections.

The Failure of Epistemology

It seems pretty obvious to me that somehow, epistemology has lost its way in the West, at least. There is substantial discussion in recent analyses about a perceived downturn in educational outcomes and knowledge retention in Western countries. For instance, standardized test scores in reading, math, and science have stagnated or fallen in many nations, including the U.S., where national assessments show declines since the 1990s, exacerbated post-COVID. Critics argue this reflects systemic failures: outdated curricula that prioritize standardized testing over critical thinking, inadequate teacher training, and a shift away from core subjects like history and civics. In Europe, similar issues emerge, with reports highlighting school failure linked to socioeconomic disparities and rigid structures that don’t adapt to modern needs. Some attribute this to a broader “dumbing down,” where rote memorization replaces deep understanding, leading to lower civic knowledge among youth.

Western democracies have faced undeniable turbulence, with rising polarization, institutional distrust, and policy gridlock. In the U.S., for example, public faith in government has plummeted since the 1970s, hitting lows amid events like the Iraq War, financial crises, and recent elections. Europe grapples with similar issues: Brexit, populist surges in Italy and France, and EU fragmentation over migration and economics. Critics describe this as a “decline of democracy,” where elites fail to address inequality, leading to voter disillusionment and authoritarian leanings. Globally, the West’s influence wanes as non-Western powers rise, with missteps in foreign policy accelerating this.

It appears that we are experiencing an ‘epistemic rebellion’ where facts fracture along partisan lines, eroding shared reality. Can we trace this back to epistemology? Since the 1980s, influences like postmodernism, relativism, and critical theory have gained prominence, challenging traditional notions of objective truth. Postmodernism, popularized by thinkers like Foucault and Derrida, emphasizes that knowledge is socially constructed, power-laden, and relative—rejecting universal truths in favor of multiple perspectives. Critical theory extends this to critique structures of oppression, influencing academia and activism. All of these influences appear to have fostered relativism, where facts become subjective, enabling misinformation and identity-based “gnosis” over evidence. If knowledge is seen as fluid, education might prioritize “lived experience” over facts, and politics devolves into echo chambers. This has led to what we see as postmodern shifts eroding objective morality and truth in universities since the 1940s–1960s, leading to societal nihilism. The social sciences have become “threats to free society” via dogmatic critical theory. Critics of this narrative defend these shifts as progressive, enabling marginalized voices and critiquing flawed “objective” systems (e.g., biased science). Alternatives like critical realism propose balancing relativism with empirical rigor. If epistemology plays a role, it might be in how we’ve prioritized subjective narratives over rigorous evidence.

Of course, the old epistemology had issues which made it susceptible to being overtaken and dismantled by the so-called progressives. A long time ago, it was thought that the Sun circled around the Earth (and the Earth was flat). We now know that isn’t true. But, at the time, it was considered to be secure knowledge; it was thought to be true, it was based on observations as far as they could go.

Traditional epistemology, rooted in Western philosophy (e.g., Descartes, Kant), for a long time, was shaped by male scholars in male-dominated institutions. This led to an emphasis on reason, reliance on standardized observation, and prioritizing detachment and objectivity. I’m not going all feminist here, but it is true that, for a very long time, knowledge produced by male-dominated institutions such as the academic world and science, seriously marginalized women – half of the human population on Earth. One example of this is the fact that medical research historically focused on male physiology to the detriment of women and children.

This male domination of what counts as knowledge, i.e. true, has been with us for a very long time. Aristotle, in his History of Animals (Book II, Part 3), states, “Males have more teeth than females in the case of men, sheep, goats, and swine.” This is not a direct assertion about human teeth counts but a generalization based on apparently no observation, and stating baldly that men and women differ in a particular way without evidence of actually counting teeth. Aristotle’s unverified claim exemplifies how male-dominated epistemology ignored women’s realities for a good portion of human history.

Another bit of so-called ‘knowledge’ that sends my blood pressure through the roof was the casual assumption of the medical profession that infants did not feel pain. They routinely performed surgery, including open-heart surgery, on infants utilizing only paralytics and NO pain relief, up until the 1990s, at least. Let me tell you, I was in the doctor’s office when a baby boy was circumcised and the screams and sobs of that infant will haunt me all my life. Yet the doctor stood there pronouncing sagely that infants really don’t feel pain like adults do. I didn’t believe it and I did NOT allow them to circumcise my son.

Why did they believe this insane bit of nonsense? Medical professionals truly believed that infants’ nervous systems were insufficiently developed to process pain, based on outdated neuroscientific models. Early 20th-century studies (e.g., 1940s research on neonatal reflexes) suggested infants lacked cortical pain perception, ignoring behavioral evidence like screaming and crying.

What the heck? Can you believe that?

The assumption that babies don’t feel pain was justified by studies that outright ignored the behavioral and physiological cues and adhered strongly to the abstract, male-centric scientific models over experiential evidence. The male dominated hierarchy gave value to what they called ‘objective data’ and dismissed lived experience or information given to them by caregivers who were usually women. This assumption was, in fact, NOT TRUE.

Another real howler: Woman with all kinds of symptoms such as anxiety, fatigue, neurological issues, depression, shortness of breath, fainting, sexual misconduct, and much more, were routinely diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ due to a ‘wandering womb’. Treatments included being put in insane asylums where all kinds of creative horrors were inflicted on them, or being handed over to doctors who specialized in delivering orgasms called ‘hysterical paroxysms’.

Consider also Thalidomide, which was safety tested only on men, but was then prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness. More than 10K children were born with severe birth defects as a result.

Next, lobotomies were performed on over 40K people in just the US to cure such things as depression and schizophrenia. The assumption was that brain surgery could cure behavior with no consideration whatsoever for possible long-term effects.

That’s just a few severe, even catastrophic failures of knowledge when knowledge acquisition adhered to a certain set of epistemological standards and norms. These oversights reflect systemic failures in epistemology. The problem was that male dominated institutions excluded or marginalized women’s perspectives and contribution to the sum of information. These biases needed to be addressed and I am glad they were, but once ‘feminist epistemology’ got its foot in the door, it was like letting the camel’s nose into the tent.

What we see is that limiting its scope led to failures of normative epistemology; it was a limitation in epistemological approach and application. The same applies to gender based power structures that determine what counts as knowledge, justification and truth. Analyzing systemic biases should be a function within the field itself. Epistemology, per se, in and of itself, should acknowledge, humanity as a whole, including that half which is female just as it should acknowledge racial differences in relation to health, intelligence, and so forth.

I also think that ‘gender theory’ is shaping up to be another catastrophic failure of epistemology, this time dominated by feminism.

A Brief History of Epistemology

As already noted, Epistemologists are philosophers who specialize in epistemology. The ancient Greeks, supposedly, were the first to engage in epistemology though they didn’t call it that at the time, and the debates have been hot and heavy ever since.

Early philosophers like Heraclitus and Parmenides debated the reliability of sensory perception versus rational thought. Heraclitus argued that everything is in flux, challenging stable knowledge, while Parmenides emphasized reason over senses, claiming reality is unchanging.

Through his method of questioning, Socrates explored knowledge as justified belief, emphasizing self-examination and the limits of human understanding, as seen in his famous claim, “I know that I know nothing.”

Plato formalized epistemology in works like Theaetetus, where he defined knowledge as “justified true belief” (a definition still debated today). In his Allegory of the Cave (Republic), he distinguished between sensory appearances and true knowledge of eternal Forms, accessible through reason.

Aristotle took a more empirical approach, arguing that knowledge begins with sensory experience but is refined through reason and logic. His Posterior Analytics outlined a theory of scientific knowledge based on observation, induction, and syllogistic reasoning. Too bad he didn’t apply this to counting teeth.

Pyrrho and later Skeptics like Sextus Empiricus questioned the certainty of knowledge, arguing that conflicting perceptions and beliefs make absolute knowledge unattainable, advocating suspension of judgment.

Augustine integrated Platonic ideas with Christian theology, arguing that divine illumination enables certain knowledge, as human reason alone is fallible. He emphasized faith as a source of understanding.

Thinkers like Al-Farabi, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) preserved and expanded Aristotelian epistemology. Avicenna distinguished between empirical knowledge and necessary truths known through intellect, while Averroes emphasized rational demonstration.

Thomas Aquinas synthesized Aristotle with Christian theology, arguing that knowledge arises from sensory experience processed by the intellect. He distinguished natural knowledge (from reason) from revealed knowledge (from faith).

William of Ockham’s nominalism challenged universal truths, emphasizing individual experience and skepticism about metaphysical claims, laying groundwork for later empirical approaches.

Rene Descartes sought certain knowledge to counter skepticism, famously declaring “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) in Meditations on First Philosophy. He argued that clear and distinct ideas, grounded in reason, provide foundational knowledge, establishing rationalism.

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, John Locke rejected innate ideas, proposing that the mind is a tabula rasa (blank slate) filled by sensory experience. Knowledge arises from sensation and reflection, though limited by human perception.

David Hume’s radical empiricism and skepticism in A Treatise of Human Nature questioned causality and induction, arguing that knowledge is based on impressions and ideas, with no certainty beyond immediate experience.

In Critique of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant revolutionized epistemology with his “Copernican turn,” arguing that the mind actively structures experience through categories like space and time. Knowledge is a synthesis of sensory data and a priori concepts, neither purely rationalist nor empiricist.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel viewed knowledge as a dynamic, historical process, unfolding through dialectical reasoning. In Phenomenology of Spirit, he argued that absolute knowledge emerges through the development of consciousness.

John Stuart Mill’s empiricism, in A System of Logic, emphasized inductive reasoning and scientific method, building on Hume and Locke.

American philosophers like Charles Peirce and William James introduced pragmatism, tying knowledge to practical consequences. Peirce’s “pragmatic maxim” linked belief to observable outcomes, while James emphasized experiential and functional aspects of truth.

Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore emphasized clarity and logic. Russell’s Problems of Philosophy explored knowledge by acquaintance (direct experience) versus description.

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and later Philosophical Investigations shifted focus to language’s role in shaping knowledge.

The Vienna Circle (e.g., Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap) argued that meaningful knowledge must be empirically verifiable, dismissing metaphysical claims. This view faced challenges from Karl Popper, who emphasized falsifiability in The Logic of Scientific Discovery. A simple example that explains this conflict:

Take the theory “All swans are white.”

Verifiability (Vienna Circle style): You could see thousands of white swans and say it’s “verified.” But that’s not enough—you’d need to check every swan that ever existed, which is impossible.

Falsifiability (Popper’s way): The theory is scientific because it can be falsified: Just find one black swan (which Europeans did in Australia), and it’s disproven. Science advances by trying (and often failing) to falsify ideas, leading to better theories. The important point is that the theory CAN BE falsified, not that it has been, or is. Just the potential for falsification is enough. Anything stated in such a way that it is not subject to falsification cannot be scientific.

Popper used this to critique things like Marxism or Freudian psychoanalysis, calling them pseudoscience because they could explain anything (unfalsifiable), while Einstein’s relativity made bold predictions that could be tested and potentially disproven (e.g., light bending during an eclipse).

In the early 1960s, Edmund Gettier challenged Plato’s “justified true belief” definition with cases showing that justified true beliefs could be true by luck. In the 1963 paper entitled “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”, he created what are called ‘Gettier Problems’ which show cases where a belief is true, justified, and held, yet fails to count as knowledge. According to the JTB model, a person knows something if:

The belief is true.

The person believes it.

The belief is justified.

Gettier presented scenarios where these conditions are met, but the truth of the belief relies on luck rather than a connection between justification and truth. Therefore, according to Gettier, the JTB cannot be called ‘knowledge’. Here is one of the classic examples:

The Job Applicant: Smith applies for a job and has strong evidence (justification) that Jones will get it (e.g., the boss told him). Smith also knows he has ten coins in his pocket. He forms the belief: “The person who gets the job has ten coins in their pocket.” Unbeknownst to Smith, he gets the job, not Jones, and he, quite by coincidence, indeed has ten coins in his own pocket. His belief is true, justified, and believed, but it’s true by luck, not because his justification (about Jones) was correct.

Gettier and his thought experiments sparked a debate in epistemology that is still going on along with all the other debates. (Again, I have sympathy for the 40 year book.) What appears to me to be the most promising of the solutions to the Gettier Problems is that of Timothy Williamson, who argues that knowledge is a primitive concept, not reducible to JTB or other conditions. He claims that Knowledge is a mental state distinct from belief, and Gettier cases show JTB’s limitations in capturing it. Obviously, this view is controversial because it pretty much dumps all the other solutions in the ditch. Go ahead and read up on Gettier problems. You will see that adding conditions to tighten up the JTB stance just isn’t working. Then have a look at Williamsons work, such as Knowledge and its Limits. When Williamson argues that knowledge is a “primitive” concept, he means it is fundamental and unanalyzable—it cannot be broken down or defined in terms of simpler, more basic concepts without circularity or loss of meaning. In traditional epistemology, knowledge is treated as composite (e.g., JTB), but Williamson rejects this, viewing such analyses as doomed to fail, as evidenced by Gettier problems and other counterexamples. Instead, knowledge is a “theoretical primitive”: a basic building block of epistemology, like “mass” in physics or “point” in geometry, which we understand through its role in theories rather than decomposition. Knowledge is conceptually prior to other epistemic notions. We grasp concepts like justification or evidence by reference to knowledge, not vice versa.

Thinkers like Michel Foucault and Thomas Kuhn examined knowledge as shaped by power, culture, and paradigms. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions introduced paradigm shifts, while feminist epistemologists like Sandra Harding explored how gender influences knowledge production. And it seems that it was all downhill from there.

Recent epistemology explores contextualism (knowledge depends on context, e.g., Keith DeRose), virtue epistemology (focusing on intellectual virtues, e.g., Ernest Sosa), and Bayesian epistemology (using probability to model belief updates). Social epistemology, including work by Alvin Goldman, examines collective and institutional knowledge.

Current Main Theories

Many of the issues that exercised the ancients continue to plague the field. So really, if things haven’t been sorted out in the past 2500 years, what’s 40 years to write a book?! You can see what I mean by the following list of the currently argued main theories.

Empiricism: Knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience. Key figures like John Locke and David Hume argue we gain knowledge through observation and experience, with the mind starting as a “blank slate” (tabula rasa).

Rationalism: Reason is the primary source of knowledge. Thinkers like René Descartes and Immanuel Kant emphasize innate ideas or logical reasoning as foundations for certain knowledge, independent of sensory input.

Constructivism: Knowledge is constructed through individual experiences and social interactions. Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky suggest we build understanding by actively interpreting the world, shaped by culture and context.

Skepticism: Questions the possibility of certain knowledge. Pyrrhonian skeptics (e.g., Sextus Empiricus) and Descartes’ methodological doubt challenge whether we can truly know anything, highlighting uncertainty or the limits of justification.

Pragmatism: Knowledge is tied to practical consequences and utility. Charles Peirce and William James argue that beliefs are justified if they work in practice, emphasizing experience and outcomes over absolute truth.

Coherentism: Knowledge arises from a coherent system of beliefs. Rather than a single foundation, beliefs are justified if they fit consistently within a web of interconnected ideas (e.g., W.V.O. Quine).

Foundationalism: Knowledge rests on basic, self-evident beliefs that serve as a foundation for other justified beliefs. Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” exemplifies this search for indubitable starting points.

Reliabilism: Knowledge is produced by reliable processes. Alvin Goldman suggests a belief is justified if it results from a process (e.g., perception, memory) that reliably produces true beliefs.

Social Epistemology: Knowledge is inherently social, shaped by collective practices, testimony, and institutions. Thinkers like Alvin Goldman and Miranda Fricker explore how social factors influence what we know.

Feminist Epistemology: Examines how gender influences knowledge production. Scholars like Sandra Harding critique traditional epistemology for male biases, advocating for “standpoint theory,” where marginalized perspectives yield unique insights.

Naturalized Epistemology: Knowledge should be studied scientifically. Quine argues epistemology should integrate findings from psychology and cognitive science to understand how we form beliefs.

Epistemology and Truth

As already mentioned, the study of knowledge is also, almost by definition, the study of Truth. How do we know what is true? In epistemology, knowledge is classically (Plato) defined as justified true belief (JTB). For a belief to count as knowledge, it must align with truth (correspond to reality), be believed by the individual, and be supported by adequate justification. Thus, truth is a core component of knowledge. But here things get a little sticky. There are different theories of truth!

Correspondence Theory: Truth is when a belief matches reality (e.g., “Snow is white” is true if snow is actually white). The issue then becomes, how can we truly know reality and that what we know or think we know about reality is actually what reality is?

Coherence Theory: Truth is when a belief fits consistently within a system of beliefs. That could be tricky if everything in the system is false.

Pragmatic Theory: Truth is what works or proves useful in practice. This is not too bad. I think the Universe might be self-correcting and if something doesn’t work or prove useful, try something else.

Deflationary Theory: Truth is merely a label for statements we accept, without deeper metaphysical significance. This, unfortunately, appears to be the state of the world today with endless echo chambers.

Christian Epistemology

In one subsection of my book, From Paul to Mark, I presented an analysis of Mark’s Gospel which drew heavily on Joel Marcus’s (Duke Divinity School) interpretation. Marcus argued that Mark’s epistemology was rooted in an apocalyptic worldview where true knowledge is a divine gift, revealed to select individuals (the elect) and obscured from others by God’s will. The text is grounded in Mark 4:11-12, where Jesus distinguishes between insiders (disciples) who receive the “secret of the kingdom of God” and outsiders who are deliberately blinded. This was connected to Daniel 10:20-21, Qumran texts, and Pauline theology (e.g., 2 Thess. 2:9-12), the result being a coherent framework where divine revelation trumps human reasoning or sensory experience, aligning with the apocalyptic tradition’s emphasis on unveiling hidden truths.

Gettier problems were brought up in that text, but I did not explore whether the disciples’ beliefs, even when true, fail as knowledge in the Gettier sense. The larger problems were, of course, that if knowledge depends on divine will, it’s unclear how humans can verify or justify beliefs independently if human cognition is unreliable without divine intervention. The scenario clearly presented human agency in acquiring knowledge as being severely diminished and humans as, more or less, passive recipients. Another problem is: if justification is divine revelation, and only the elect receive it, how can one distinguish true revelation from delusion? (Assuming that numerous groups would claim divine revelation, as is the case in reality.) Also, in that text, I cite 2 Thess. 2:9-12, where God sends delusion to the unrighteous, complicating the reliability of perceived revelations! If God can send both truth and delusions, who is getting what?

In FPTM, had other fish to fry so passed over the epistemological problems in favor of my goal: that the text was suggesting that there are different types of humans, some who can ‘hear and see’ and some who can’t. I think that would be a very unpopular version of reality nowadays; not very DEI for sure.

The Markan text’s claim that only those with “spiritual organs” can perceive truth risks epistemic closure, where only preordained individuals can access knowledge. This conflicts with epistemological principles like universal accessibility (DEI) and fails to explain how the elect can confirm their status without circularly relying on divine revelation. If truth is hidden from most humans and only revealed to the elect, how can it be verified? The text suggests demons and Satan also know the truth (e.g., Mark 1:24), which complicates the reliability of revelation, as malevolent beings share the same knowledge. Do the Elect have epistemic responsibilities?

Mark’s epistemology diverges from traditional theories like empiricism and rationalism. Empiricism posits that knowledge arises from sensory experience, but Mark suggests human senses are unreliable without divine revelation (e.g., Mark 4:12). Rationalism emphasizes reason, yet Mark portrays human reasoning as limited, with even the disciples misunderstanding Jesus (Mark 8:17). Instead, Mark’s epistemology aligns more closely with a form of divine reliabilism, where knowledge stems from a reliable divine process (revelation) but is contextually restricted to the elect. Unlike standard reliabilism, which evaluates belief-forming processes (e.g., perception) for general reliability, Mark’s framework requires divine selection, raising questions about accessibility and verification.

Interestingly, Gettier’s claims find an example in Mark’s narrative. Peter’s confession, “You are the Messiah” (Mark 8:29), is true and justified (based on Jesus’s miracles and teachings) but flawed because Peter misunderstands the Messiah’s suffering role (Mark 8:31-33). This resembles a Gettier case: Peter’s belief is true but not knowledge, as its truth depends on Jesus’s identity rather than Peter’s incomplete justification. Similarly, the centurion’s declaration, “Truly this man was God’s Son” (Mark 15:39), is true and possibly justified (witnessing Jesus’s death), but its status as knowledge is unclear without divine confirmation, given the apocalyptic emphasis on hidden truths. Mark’s epistemology implicitly addresses this by suggesting that true knowledge requires not just justification but divine alignment, where the believer’s understanding matches God’s intent. However, this raises a problem: if justification depends solely on divine revelation, how can the elect verify their beliefs without circularly relying on God’s will?

In the Markan text, human agency is limited but not absent. Mark 4:9, “Let anyone with ears to hear listen,” and Mark 13:33-37, urging watchfulness, suggest the elect must actively respond to divine revelation. For example, the Parable of the Sower (Mark 4:1-20) implies that only “good soil” (those chosen by God) can receive the word, yet the exhortation to “hear” suggests some agency in cultivating receptivity.

Mark’s epistemology aligns with a correspondence theory of truth, where truth reflects divine reality. However, verification is problematic: demons also know Jesus’s identity (Mark 1:24), suggesting supernatural knowledge isn’t inherently trustworthy. The text’s apocalyptic view—that full truth awaits the eschaton (1 Cor. 13:12)—complicates pragmatic theories, where truth is what works in practice. The disciples’ partial understanding (e.g., Mark 8:17) lacks immediate utility, reinforcing the eschatological focus.

Marcus describes Mark’s epistemology as a “collision of kingdoms” (p. 567), where God’s kingdom, revealed through Jesus, opposes Satan’s, which blinds humanity. The Parable of the Sower (Mark 4:1-20) illustrates this: the “word” (God’s truth) flourishes in “good soil” but is thwarted by Satan’s agents (e.g., worldly cares). The Parable of the Strong Man (Mark 3:23-30) reinforces this, depicting Jesus as plundering Satan’s house, retrieving the elect. The unforgivable sin (blasphemy against the Holy Spirit) underscores the stakes: rejecting divine revelation aligns one with Satan. This cosmic battle peaks at the cross (Mark 15:39), where the centurion’s recognition of Jesus as the Son of God marks the first human acknowledgment of the full truth. Marcus argues this signals the “turn of the ages” (p. 574), though false prophets (Mark 13:22) suggest Satan’s influence persists. The elect must remain vigilant, aligning with the limited agency noted above.

The disciples’ persistent incomprehension (e.g., Mark 6:52, 8:17, 14:68-71) highlights the limits of human knowledge, even among the elect. Peter’s denials (Mark 14:68, 71) echo the “outsiders’” blindness, suggesting that divine revelation is imperfect until the eschaton. This aligns with Qumran texts (1QS 9:18), where even the righteous can be led astray. The partially healed blind man (Mark 8:24) symbolizes this, seeing “men as trees, walking,” reflecting the disciples’ incomplete grasp. (Marcus, J. (1984)“Mark 4:10-12 and Markan Epistemology.” Journal of Biblical Literature, 103.4, pp. 557–74.)

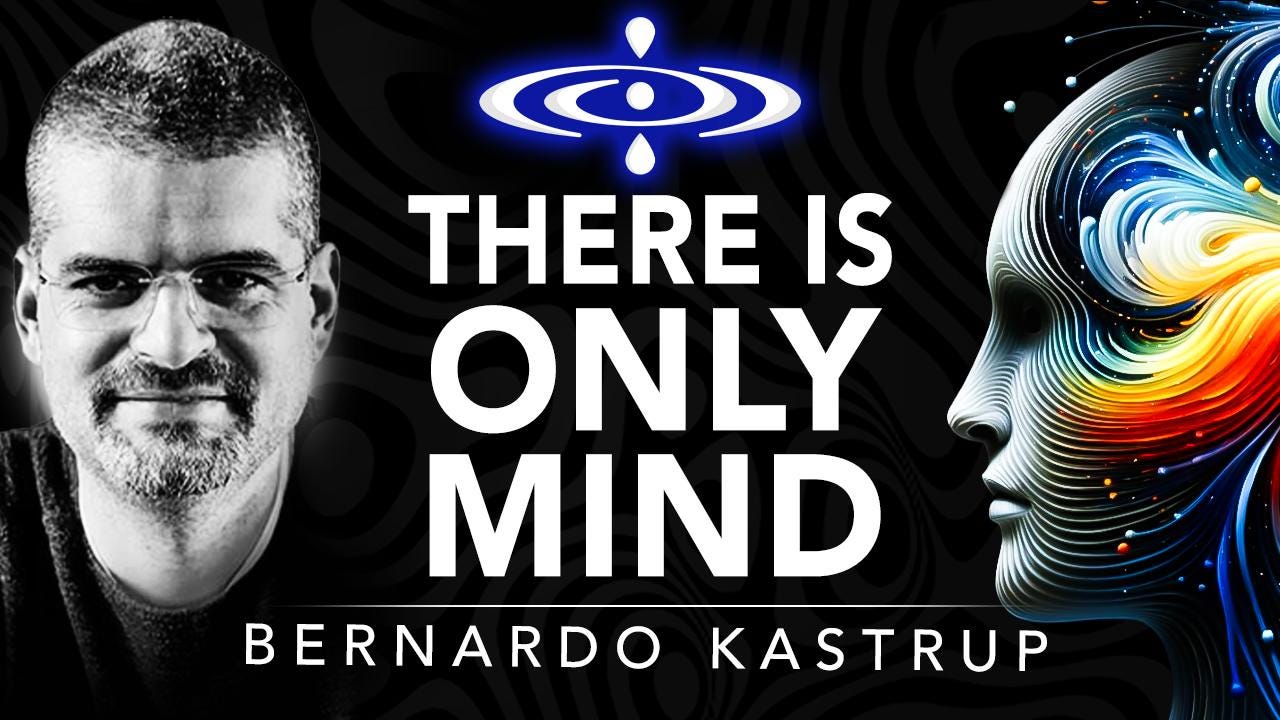

The Idea of the World

More or less in the same spirit as the work of Timothy Williamson, Bernardo Kastrup’s The Idea of the World (2019) presents a metaphysical framework of analytic idealism, positing that reality is fundamentally mental—a universal consciousness or “mind-at-large” (MAL)—and that physical phenomena, including the material world and individual minds, are dissociated expressions (or “alters”) of this singular consciousness. Kastrup argues that what we perceive as the physical universe is the “image” of mental processes within MAL, akin to a dream, with empirical observations (e.g., quantum mechanics, neuroscience) better explained by idealism than materialism. Individual minds are localized dissociations of MAL, experiencing reality through a filtered interface, and true knowledge involves accessing the underlying mental reality beyond sensory appearances.

Kastrup’s core claims reshape the foundations of epistemology:

According to Kastrup, the physical world is an extrinsic appearance of mental processes in MAL. Physical events are like desktop representations of deeper mental dynamics, not independent material facts. That is, physical phenomena are symbols of thoughts in MAL.

Kastrup further proposes that individual human minds are like dissociative identity disorder (DID) alters within MAL, with limited access to universal consciousness. True knowledge involves transcending the dissociative boundary to access MAL’s intrinsic mental states, akin to “waking up” from a dream. There are limits to empiricism in Kastrup’s model. Sensory data (the “desktop”) is a filtered representation, prone to distortion. Neuroscience supports this: perception is a brain-constructed model, not raw reality.

Kastrup’s ideas will be the topic of the next post. They are so sensible and compelling, I want to discuss them in detail because they play a role in arguments of my own that I will get to after. And yes, I AM circling around to the Hyperdimensional Control System hypothesis and what happens to epistemology in the face of marauding Overlords of Entropy.

What a great topic! I remember being fascinated by epistemology when I first studied it at school, and then, getting the feeling that it was all going towards nonesense in the end (with postmodernism and all that) but there seems to be still some interesting thinkers that may help us think and understand knowledge and truth more.

The problem of 'revelation' or 'inspired knowledge' is a deep one and one that many thinkers don't dare look into because of the materialistic imposition on all fields of knowledge we have. When reading your post I can't help but admire how you don't mind going where not many people want to go, connecting different fields and giving us kind of like a mosaic understanding of every subject you look into. Thank you for that once again!

Now, adding just my tiny bit of thought, what's very interesting about Kastrup's idea of MAL being something like a consciousnes with DID and us being like 'parts' of it, is that in Psychology there's the idea of the multiplicity of mind too, which doesn't refer to people with DID only but to all of us who, according to this view, also have inner parts of ourselves that have limited awareness of us as whole consciousness, so to speak. And the reason I find that interesting is that there's this idea that our own minds are a reflection of the reality in some way, or to say it in the cliche way, "as above so below", so perhaps there's something to be learned in how this inner multiplicity plays out that can help us learn how this potential MAL plays out too.

Thank you for the article, Laura. I would like to share a couple of ideas on the subject, but they are not really related to what is discussed in the article. I will try to be brief and concise, using Grok, given its usefulness for creating good summaries.

The article has brought to mind a very important aspect of traditional spirituality: creative imagination, a term coined by Henri Corbin to refer to the alam al mithal often mentioned by Ibn Arabi. If you are interested in Ibn Arabi and like Chittick, in case you haven't read it, I recommend reading “Imaginal Worlds: Ibn Al-'Arabi and the Problem of Religious Diversity,” where he discusses the subject at length, and of course Henri Corbin's work on creative imagination. At least for me personally, it has helped me understand the variability of perception, understanding, and interpretation of reality.

For example, from that perspective, the Cassiopaea Experiment would be an imaginal practice that allows information to be “translated” into concrete forms that are apprehensible to participants to the extent that they are capable of translating (levels of being). To avoid going on too long, I asked Grok if there is a relationship between creative imagination and epistemology and in what way (I gave Ibn Arabi, Corbin, and Proclus as examples of authors who spoke extensively on the subject):

Grok:

Yes, the creative imagination—as developed by Henry Corbin, Ibn Arabi, and Proclus—maintains a profound and central relationship with epistemology, particularly in the realm of perennial philosophy, Neoplatonism, and Sufi theosophy. Below, I'll explain this connection succinctly, based on key interpretations.

The Concept of Creative Imagination

The "creative imagination" (or khayāl in Arabic, phantasia in Greek) is not mere reproductive fantasy, but an active epistemological organ that mediates between the sensible (material) world and the intelligible (spiritual) one. It enables access to intermediate realities—the 'alam al-mithal or "imaginal world"—where divine truths manifest as theophanies (symbolic appearances). This resolves classic epistemological tensions, such as the gap between faith and reason, or sensory perception and intuitive knowledge.

Relationship to Epistemology

In epistemological terms, this imagination functions as a mode of participatory and visionary knowledge, not merely rational or empirical. It facilitates:

Theophanic Perception: Knowledge arises from direct experience (shuhūd or vision), where the spiritual "incarnates" and the corporeal spiritualizes, enabling personal and dialogical gnosis (ma'rifa).

Symbolic Hermeneutics (ta'wil): It transmutes sensory data into symbols that reveal hidden essences (bāṭin behind ẓāhir), elevating knowledge to esoteric levels with seven degrees of interpretation.

Resolution of Paradoxes: Such as "seeing the invisible" (e.g., God without form), aligning with a transconscious phenomenology that integrates intuition (dhawq), cosmic sympathy (sympatheia), and the heart's creative projection (himma).

Contributions of the Authors

Ibn Arabi (1165-1240): In his Sufism, imagination is the "Imaginatrix" (Hadrat al-Khayāl), an organ of the heart with "two eyes" (reason and imagination). Its balanced mastery avoids perceptual distortions; it is key to self-knowledge ("He who knows himself knows his Lord") and recurrent theophany, where knowledge is co-creation with the divine.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978): He interprets this imagination as a gnostic bridge in esoteric Islam (Shi'i and Sufi), contrasting it with Averroist rationalism. In his work Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabi, he links it to prophetic epistemology: the contemplative prophet accesses eternal truths via subsistent images, integrating Neoplatonism and revelation.

Proclus (412-485): In Neoplatonism, imagination is a "creative and salvific" faculty in angelic hierarchies, freed from sensory deficiencies. It influences Ibn Arabi via Islamic Neoplatonism (Avicenna, Suhrawardi): it mediates cosmic sympathy (e.g., heliotropism as natural prayer) and emanation, making knowledge an act of cosmic homologation and creative renewal.

In summary, this imagination is not peripheral but essential to an integral epistemology that transcends empiricism and formal logic, opening human beings to multidimensional realities.

--

That was all it was, a thought to share.